A common refrain by mainstream economists is that substantial federal government spending (and its corresponding debt and interest on the debt) is unsustainable in the long term, and potentially catastrophic. Modern Money Theory, or MMT, demonstrates that government spending on public purpose is possible to a much, much greater extent than we are led to believe[see the footnote at the very bottom of this post] – indeed, not just safe but highly beneficial to the macroeconomy, not to mention, desperately needed by millions. Because of this, the concern for fiscal sustainability is often levied against the MMT project itself.

This post summarizes the mainstream concern, lists the main assumptions that underlie it, and provides several academic sources to address the argument as a whole and each assumption. (Basically, they're all bunk.)

(This post was inspired by my February 2021 interview with Danish PhD candidate Asker Voldsgaard and German PhD economist Dirk Ehnts, co-authors of the 2020 paper A Paradigm Lost, a Paradigm Regained – A Reply to Druedahl on Modern Monetary Theory. The paper being responded to is the 2019 paper by Danish PhD. economist Jeppe Druedahl, called A Kinder Egg on MMT, in which a primary concern about MMT is that in the long-term, were its insights applied, it could prove fiscally unsustainable.)

| Related post: Government deficits *augment* private spending. (There’s no such thing as “crowding out.”) |

|

GO BACK TO ALL MMT RESOURCES

This post was last updated November 3, 2022. Disclaimer: I have studied MMT since February of 2018. I’m not an economist or academic and I don’t speak for the MMT project. The information in this post is my best understanding but in order to ensure accuracy, you should rely on the expert sources linked throughout. If you have feedback to improve this post, please get in touch. |

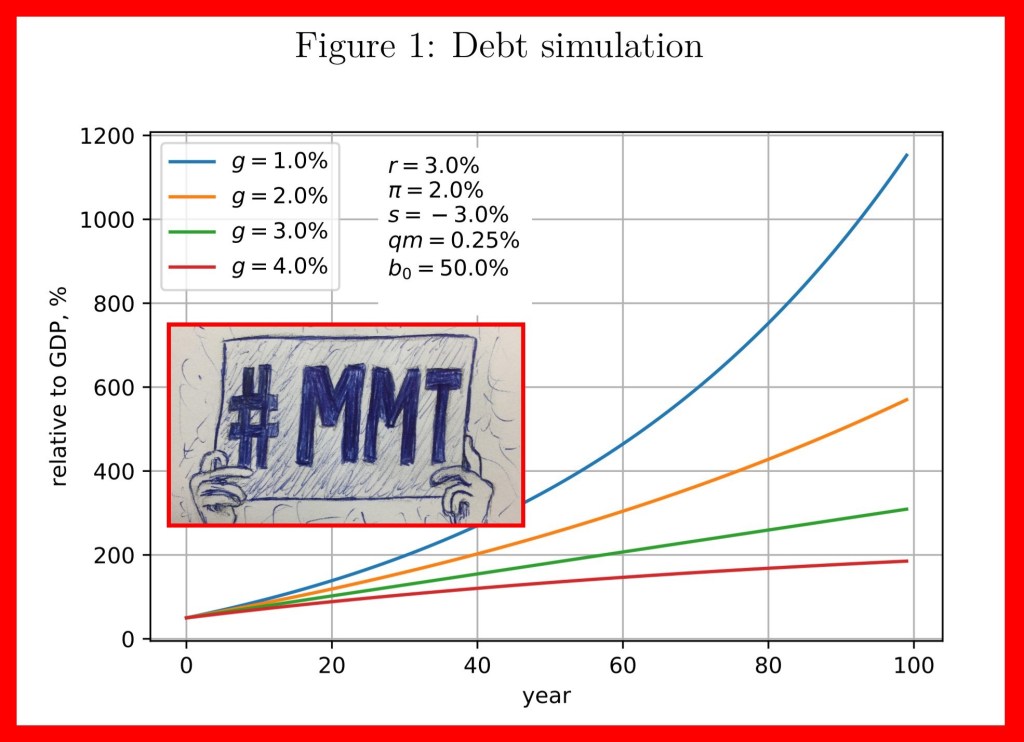

The mainstream argument regarding long-term fiscal sustainability is made, for example, in this 2019 paper by Danish PhD. economist Jeppe Druedahl, called A Kinder Egg on MMT. It concludes that when government spending (and its debt and interest) is modeled out to the next 75-100 years, there is a very real possibility that it will result in an “exploding debt ratio” or “exponential rise in the interest on the debt.” This would force the government to face a stark choice, both of which would result in Economic Armageddon: they must either:

- Issue currency to pay off the approaching-infinite interest, which would cause hyperinflation, or

- Choose to default on those interest payments in order to avoid that hyperinflation.

Regarding the latter, according to the United States Treasury:

A default would be unprecedented and has the potential to be catastrophic: credit markets could freeze, the value of the dollar could plummet, U.S. interest rates could skyrocket, the negative spillovers could reverberate around the world, and there might be a financial crisis and recession that could echo the events of 2008 or worse. […]

[A default] could have a catastrophic effect on not just financial markets but also on job creation, consumer spending and economic growth—with many private-sector analysts believing that it would lead to events of the magnitude of late 2008 or worse, and the result then was a recession more severe than any seen since the Great Depression. Considering the experience of countries around that world that have defaulted on their debt, not only might the economic consequences of default be profound, those consequences, including high interest rates, reduced investment, higher debt payments, and slow economic growth, could last for more than a generation.

The mainstream case depends on all the following assumptions:

- Loanable funds: The idea that banks can only loan out other people's money, to citizens and businesses in the non-government sector, and to the government.

- It is possible for the central government (the one and only issuer of the currency) to borrow its own money from commercial banks (in the same sense as currency users), hold that money, and then use it for future respending.

- Crowding out: The non-government sector must compete with the government for that limited pot of loanable funds.

- Although the shortest-term interest rate (the “nominal” target rate) is set by the central bank, rates at longer-time horizons are set by “real” forces in the market, and the central bank is helpless to stop it. This is substantially due to the limited availability of loanable funds.

- It is possible to predict the size of the federal deficit (and corresponding debt and interest) for the next 75-100 years.

- The interest on the debt might become so intergalactically large that the issuer of the currency may choose to default in order to avoid the potential hyperinflation.

- There is full employment, either right now, or soon-to-be. When there is full employment, then issuing new currency does indeed pose a potential inflationary danger, because there’s nothing left to buy!

None these assumptions represent the world we actually live in. The reality is that:

1. Loanable funds

With little exception, banks create money every time they lend. Here's a walkthrough by Texas Christian University economics professor, and Cowboy Economist, John Harvey: (video, audio). More from Bill Mitchell, Professor in Economics and Director of the Centre of Full Employment and Equity (CofFEE), at the University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia. From his 2009 post, The IMF fall into a loanable funds black hole … again:

There is no finite pool of saving that different borrowers compete for and thus drive interest rates up when borrowing demands increase. That view was discredited in the 1930s by Keynes (and others). It is based on the loanable funds doctrine which was the mainstay of the neo-classical marginalists. It assumes saving is a function of interest rates rather than income. It assumes that investment (or other sources of spending that relies on borrowing) is constrained by the available pool of saving.

We understand that none of those assumptions or propositions are even slightly correct.

2. It is possible for the central government (the one and only issuer of the currency) to borrow its own money from commercial banks (in the same sense as currency users), hold that money, and then use it for future respending.

Just as banks always lend money into existence, the federal government, without any exception, always spends money into existence. Here is the entire abstract from Stephanie Kelton's 1998 paper, Can Taxes and Bonds Finance Government Spending? (emphasis added):

This paper investigates the commonly held belief that government spending is normally financed through a combination of taxes and bond sales. The argument is a technical one and requires a detailed analysis of reserve accounting at the central bank. After carefully considering the complexities of reserve accounting, it is argued that the proceeds from taxation and bond sales are technically incapable of financing government spending and that modern governments actually finance all of their spending through the direct creation of high-powered money. The analysis carries significant implications for fiscal as well as monetary policy.

(Would appreciate assistance in finding equivalents for other countries….)

In addition:

- Banks are explicitly licensed, or franchised, by the government to issue loans. The idea that the government must borrow its own money from an institution that only it can bestow this power onto, is nonsensical.

- Article 1, section 8 of the Constitution of the United States makes it clear that only Congress can issue the dollar (and delegate this power to other entities).

- The idea that the the central bank is not under the control of the government ignores the fact that, without rewriting the Constitution, it is impossible for Congress to create something that it cannot subsequently alter or uncreate. Any independence the central bank has is only because members of Congress choose to look the other way.

3. Crowding out

Government spending doesn't crowd out private (non-government) sector spending, it augments it. Real crowding out is possible, financial crowding out is not. This concept is thoroughly addressed in this post: Government deficits *augment* private spending. (There's no such thing as “crowding out.”)

As an example, here's investor Mike Norman, in this 2013 video, Government spending does not “crowd out” private sector investment. Here's why…

Crowding out means when the government has to borrow money then that takes funds away from the private sector which could have been used for productive investment. Now this is all completely wrong, of course, as we know, because the government issues its own money the money when it spends it. […]

4. Interest rates at longer time horizons are set by “real” forces in the market, and the central bank is helpless to stop it.

The interest rate at all time horizons is virtually 100% in the control of the central bank. The voting members at the FOMC Board at the Federal Reserve decide on a target rate, announce it, and then stand ready to buy or sell literally any amount of bonds, at any time, in order to defend that rate. This is elaborated on in a 2020 paper by Scott Fullwiler, When the Interest Rate on the National Debt Is a Policy Variable (and “Printing Money” Does Not Apply).

(There are equivalents in all sovereign economies, such as Canada, Australia, Japan, the U.K., and etc.)

5. It is possible to predict the size of the federal deficit (and corresponding debt and interest) for the next 75-100 years.

The idea that we can predict what government spending will be even one year in the future, let alone 100, is absurd on its face.

6. The interest on the debt might become so large that the issuer of the currency may choose to default in order to avoid the potential hyperinflation.

The idea that the interest in the debt, no matter how intergalactic its size, somehow can't be paid (or would be harmful), is false. From the 1943 paper by Abba Lerner, Functional Finance and the Federal Debt (emphasis added):

This means that the absolute size of the national debt does not matter at all, and that however large the interest payments that have to be made, these do not constitute any burden upon society as a whole. A completely fantastic exaggeration may illustrate the point. Suppose the national debt reaches the stupendous total of ten thousand billion dollars (that is, ten trillion, $10,000,000,000,000), so that the interest on it is 300 billion a year. Suppose the real national income of goods and services which can be produced by the economy when fully employed is 150 billion. The interest alone, therefore, comes to twice the real national income. There is no doubt that a debt of this size would be called “unreasonable.” But even in this fantastic case the payment of the interest constitutes no burden on society. Although the real income is only 150 billion dollars the money income is 450 billion150 billion in income from the production of goods and services and 300 billion in income from ownership of the government bonds which constitute the national debt. Of this money income of 450 billion, 300 billion has to be collected in taxes by the government for interest payments (if 10 trillion is the legal debt limit), but after payment of these taxes there remains 150 billion dollars in the hands of the taxpayers, and this is enough to pay for all the goods and services that the economy can produce. Indeed it would do the public no good to have any more money left after tax payments, because if it spent more than 150 billion dollars it would merely be raising the prices of the goods bought. It would not be able to obtain more goods to consume than the country is able to produce.

7. There is full employment, either right now, or soon-to-be.

As Dirk Ehnts told me (in episode 66 of Activist #MMT), we haven’t had full employment in the United States since at least World War II. On a very-related note, unemployment statistics in the US are overly rosy.

In conclusion

The long-term fiscal sustainability of the federal government (of fully-financially-sovereign currencies), the one and only issuer of the currency (and bonds), can only be in doubt in a fantasy world, not reality.

General, overall responses by MMTers, to the mainstream concern of the long-term fiscal sustainability of government spending

- A direct and detailed response can be found in this 2020 paper by Danish PhD candidate Asker Voldsgaard and German PhD economist Dirk Ehnts, A Paradigm Lost, a Paradigm Regained – A Reply to Druedahl on Modern Monetary Theory. (Here’s my interview with Dirk and Asker on this paper, which was the inspiration for this post.)

- Here are earlier papers by Scott Fullwiler (that are kind-of precursors to his 2020 paper as linked above):

- A 2011 paper by James Galbraith: Is the Federal Debt Unsustainable?

- A May 2020 Financial Times article by Stephanie Kelton: Can governments afford the debts they are piling up to stabilise economies?

- Canadian bond trader Brian Romanchuk:

- 2016 by Heteconomist: MMT 101 – Modern Monetary Theory on “Fiscal Sustainability”

Footnote (regarding the very first paragraph)

MMT says much greater spending by fully-financially-sovereign currencies [such as the US, U.K., Australia, Canada, Japan, and etc.], for public purpose, is safe in general, not specifically in the long-term. You can't know what spending is safe until you (a) decide what to do and (b) look into it. For example, here are four inflationary and resource-impact studies demonstrating all the following would be not just safe but highly beneficial: Medicare For All, cancelling all student debt, a truly bold Green New Deal, and the MMT-designed job guarantee. To be clear, however, the MMT project recommends three policies, no more, no less: a floating exchange rate, a [its!] job guarantee, and ZIRP.)

TOP IMAGE: From Jeppe Druedahl's 2019 paper.

This post was originally a Twitter thread, which was inspired by Dinah Poelnitz.